Cornwall is a small, strangely-quaint coal mining town in the Fingal Valley, North-East Tasmania, not far from Avoca.

Coal was first discovered at Cornwall in 1843 when a farmhand from nearby Woodlawn went hunting in the hills and found his dog, digging in a wombat hole, had scratched out coal.

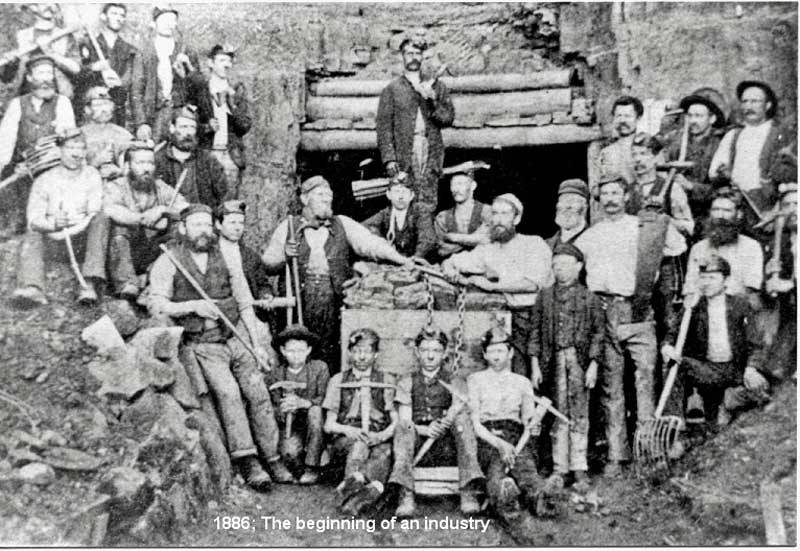

However it wasn't until 1886 when the railway was opened between Conara and St Marys that The Cornwall Coal Co. was formed and coal production began at Cornwall, hence the town evolved from what began as a camp with a few huts and a tent or two.

The Cornwall Coal Company is the only supplier of coal mined in Tasmania.

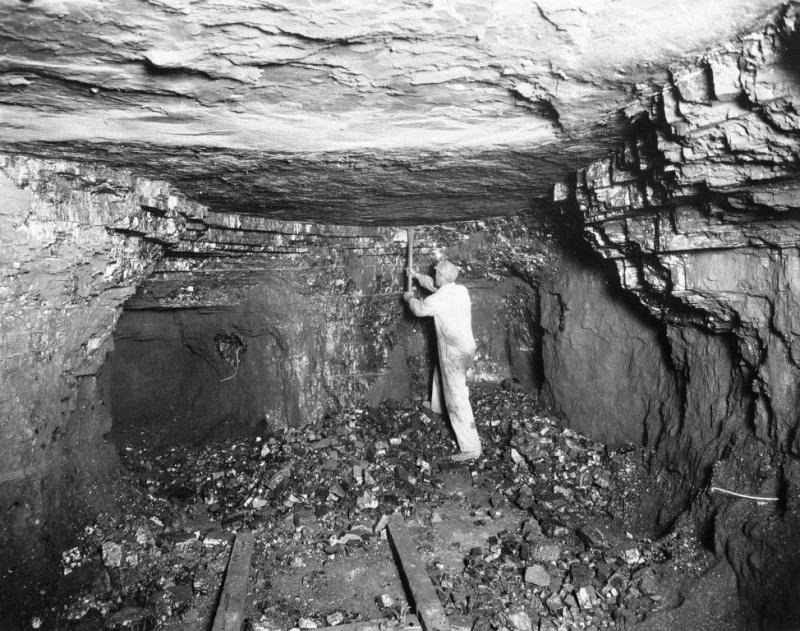

The company currently mines black coal from underground and open cut mines from where the product is transported to a washery at Duncan Siding near Fingal, from the Duncan Colliery at Fingal, and from Kimbolton in southeast Tasmania.

The Blackwood mine, also known as the Cornwall colliery, is run by the Cornwall Coal Company.

The major consumers of Tasmanian coal are currently the (parent company) Cement Australia plant at Railton and the Norske Skog newsprint mill at Boyer on the Derwent River near New Norfolk.

Production of raw coal in 2009 and 2010 totalled 646,148 tonnes, with 372,441t of saleable coal produced.

Worker’s compensation

Between 1980 and 1990 there were about 200 accidents reported each year and the company paid between $50,000 and $250,000 per annum in compensation to mine workers.

Then in 1991/92 the accident rate started to dip dramatically, so by 1993 it was practically zero and it has remained near zero. The value of compensation fell to almost zero.

So how did it happen?

Did the mine close in 1993?

No.

A Christian mine manager, Bob Mellows, saw safety was best regulated not by the law of the land, but by the law of Love.

He made a study of the practical meaning of the word love in the New Testament and shared his findings with the miners.

He spoke to his men about how different the workplace would be if they treated each other in a way consistent with the teachings of Jesus. If they were humble and owned up to their mistakes and took responsibility for them and for each other, if they cared for one another, and put the interests of others ahead of their own.

1998 Coal Miner’s Conference

In a report to the ’98 Coal Operator’s Conference, he said: ‘It is not because of legalism that Jesus Christ told us to love God and love one another. It was because he knew it was essential to our well-being in all aspects of life.’

He went on to say, ‘The Foundation of Safety is loving one another (and ourselves). This is not merely an emotional condition. It is a choice of behaviour and the only basis for a satisfactory relationship.’

The Cornwall Mine’s safety improved, Mellows concluded, when a breakthrough in relationships occurred, when barriers were removed, trust developed, and self-esteem achieved, and this breakthrough occurs whenever communities resolve to live by the values of Jesus.

.jpg) John Skinner is a retired journalist who has written ten biographies on famous campdrafting competitors. He was an Australian infantry soldier wounded in Vietnam, served six years as a Police Officer, was CEO of the then Australian Rough Riders Assn (Pro-Rodeo based in Warwick, Qld). He and his wife Marion retired to a small farm 25km south of Warwick 20 years ago. They have three children and now seven grandchildren.

John Skinner is a retired journalist who has written ten biographies on famous campdrafting competitors. He was an Australian infantry soldier wounded in Vietnam, served six years as a Police Officer, was CEO of the then Australian Rough Riders Assn (Pro-Rodeo based in Warwick, Qld). He and his wife Marion retired to a small farm 25km south of Warwick 20 years ago. They have three children and now seven grandchildren.

John Skinner served as an infantry soldier in Vietnam then the Tasmanian Police before taking up the position of CEO of the Australian Rough Riders Association (professional rodeo based in Warwick Qld). Before retirement to his small farm, he was a photo-journalist for 25 years. He is married with 3 children and 7 grandchildren.