QARA KELISA, Iran - The last priest left the Black Church more than half a century ago and now the picture on the wall of a former monk's cell is of the Islamic Republic's founder Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, not Jesus.

But Iran says this medieval Armenian Christian retreat in a mountainous region close to Turkey and Armenia shows it is observing the rights of other faiths.

It denies charges from Iran's old foe the United States that it discrimates against Christian and other religious minorities. The Armenian bishop in Tehran tells Reuters such talk is a Western "innovation".

The Shi'ite Muslim country has applied for Qara Kelisa, or the Black Church, to be recognised as a United Nations World Heritage site, to join the Persepolis and other archaeological treasures.

"This is a symbol of the co-existence of different religions and ethnicities," said senior conservationist Khosro Farri of Iran's Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organisation.

The numbers of Christians and Jews in Iran have dwindled since the 1979 Islamic revolution, and people who are members of minorities can be reluctant to speak when asked how the authorities deal with them.

But several Armenians in this northwest region said they were treated like any other Iranian.

"I don't have any problems living here," said Aldagesh Malik, an elderly Armenian man in the village of Gardabad, a three-hour drive south of the church.

His village used to have a majority Armenian population but most have moved in search of a better future in Iran's cities or abroad -- some as far as the United States.

Sitting and chatting with a Muslim neighbour, Malik said: "Your religion doesn't make any difference. We are all friends."

MUSLIM GUARDS

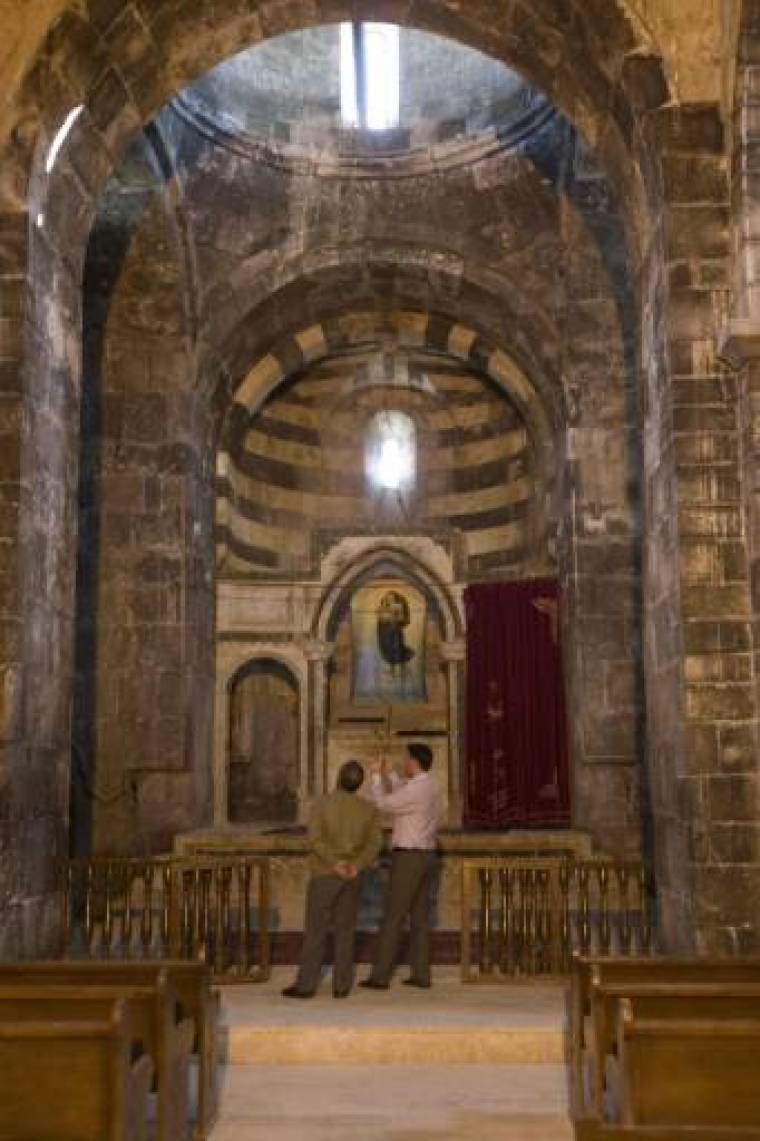

Located in tawny hills, the Black Church derives its name from the volcanic stone used to build it in the early 14th century after an older one was destroyed by an earthquake.

Armenians -- members of an ancient independent branch of Christianity -- believe one of Jesus' apostles, St Jude, was martyred and then buried where the church now stands. Its distinctive black-and-white striped tower is visible from afar.

Many of those who lived here fled the turbulent border region in World War One, when Armenia says 1.5 million ethnic Armenians were killed in a 1915 "genocide" by Ottoman armies in what is now Turkey. Ankara denies any systematic killings.

The church is now mostly empty of Christian worshippers -- two Sunni Muslims from a nearby Kurdish village guard it -- but thousands of Armenians from around the world flock here every summer for festivities to commemorate their patron saint, also known as Thaddeus.

Officially named St Thaddeus, the church's focus in Iran's World Heritage bid is, said Farri, a sign of its respect for other religions. He said Armenian pilgrims to the site are "completely free to do what they want".

Amnesty International this year said minorities in Iran were subject to discriminatory laws and practices. It focused on the treatment of Baha'is, seen by Iran's religious leaders as a heretical offshoot of Islam. It also said several evangelical Christians, mostly converts from Islam, were detained in 2006.

The U.S. State Department said in a March report that all religious minorities suffered varying degrees of discrimination in Iran, particularly in employment, education and housing.

But Sebouh Sarkissian, the Armenian archbishop in Tehran, dismissed such allegations as an "innovation from the West".

"People are coming and always asking: is there discrimination in this country?" said the black-robed prelate in his office next to the 20th century Armenian cathedral in Iran's capital. "I can tell you that I've felt discrimination even in the United States, even in Europe."

DWINDLING COMMUNITY

Armenians are recognised in Iranian law. They have two seats assigned to them in the 290-seat parliament and can educate their children in the Armenian language. They can even make and drink alcohol at home -- a practice banned for Muslims.

Nonetheless, the community has continued to shrink since the Islamic revolution almost three decades ago.

Once estimated to have numbered several hundred thousands, it is now only about 100,000 strong, said Sarkissian citing a figure from the official IRNA news agency.

"The process of migration regarding the Armenian community started even before the revolution," he said. "Immigration and migration, it is a phenomenon all over the world ... not anything peculiar to Iran and Iranian society.

"Even Iranians are emigrating from this country, not only Christians, not only Armenians."

He acknowledged Armenians in Iran could face problems: for example, Armenian schools must use a religious book prepared by the government. But he praised the authorities for seeking World Heritage status for the Black Church and for renovating it.

A light-coloured section of the church was added 200 years ago. Saints slaying dragons and devils and other elaborate motifs are carved in white stone.

Visiting from a nearby town, Kheyrollah Mahmoudi said his grandmother and other Armenians fleeing Turkey hid there nine decades ago. She later married a Muslim man in Iran.

"They were all afraid they would be killed," Mahmoudi said, recalling the old stories as he stood gazing at the church in the sunlight. "It is like a movie in front of my eyes."