In Genesis, God promised Abraham that his descendants would become "a great nation," but the line begins with Jacob, Abraham's grandson. Jacob's favorite son, Joseph, does not have a tribe bearing his name. Instead, Joseph's two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, are blessed by Jacob as his own and each fathers a separate "tribe." The Menashes are descendants of Menasseh.

According to an Israeli organization formerly called Amishav — "My people return" — there are 1 million to 2 million Bnei Menashes living in the hilly regions of Burma and northeast India.

After an Assyrian invasion circa 722 B.C., Jewish tradition says 10 tribes from the northern part of the kingdom of Israel were enslaved in Assyria. Later the tribes fled Assyria and wandered through Afghanistan, Tibet and China.

About 100 A.D. one group moved south from China and settled around northeast India and Burma. These Chin-Mizo-Kuki people, who speak Tibeto-Burmese dialects and resemble Mongols in appearance, are believed to be the Bnei Menashes.

Although many Bnei Menashe want to "return" to Israel, only about 800 have been able to emigrate there in the past few years. Israeli visas were denied to most others.

Shavei Israel, a Jerusalem-based organization that has been trying to locate descendants of lost Jewish tribes around the world and bring them to Israel, believes that all Chins in Burma, Minos in Mizoram and Kukis in Manipur — three prominent tribes of South Asia — are descendants of Menashe.

According Shavei Israel, India has more than a million people who are ethnically Bnei Menashes. Because they lived for centuries in northeast India, mingling with local people, many of their Jewish traditions became diluted. And after Welsh missionaries arrived in the area in 1894, nearly all Indian Bnei Menashes converted from their animistic beliefs to Christianity.

In the early 1970s, some Kuki and Mizo Christians noticed that many of their customs — like male circumcision, animal sacrifices, burial customs, marriage and divorce procedures, observation of the Sabbath and the symbolic use of the number 7 in many festivals — were similar to those of Jews around the world.

DNA studies at Central Forensic Institute in Calcutta also concluded that while the tribe's males showed no links to Israel, the females share a family relationship to the genetic profile of Middle Eastern people. The genetic difference between the sexes might be explained by the marriage of a woman who came from the Middle East to a man of Indian ancestry.

Further genetic studies on the Indian tribes are continuing at the University of Arizona and the Technion Institute in Haifa, Israel.

Last March, Shlomo Amar, the Sephardic chief rabbi, announced in Jerusalem that he accepted the Bnei Menashe as one of the 10 "lost tribes" of Israel.

Rabbi Eliyahu Birnbaum, a dayan or rabbinical court judge and spokesman for Rabbi Shlomo Amar, said the decision to accept Indian Bnei Menashes as a lost Jewish tribe followed a careful study of the issue.

"The chief rabbi sent a delegation of two dayanim [judges] to India last year to conduct a thorough investigation of the community and its origins." After that, "it was decided that the Bnei Menashes are in fact descendants of Israel and should be drawn closer to the Jewish people," said Mr. Birnbaum.

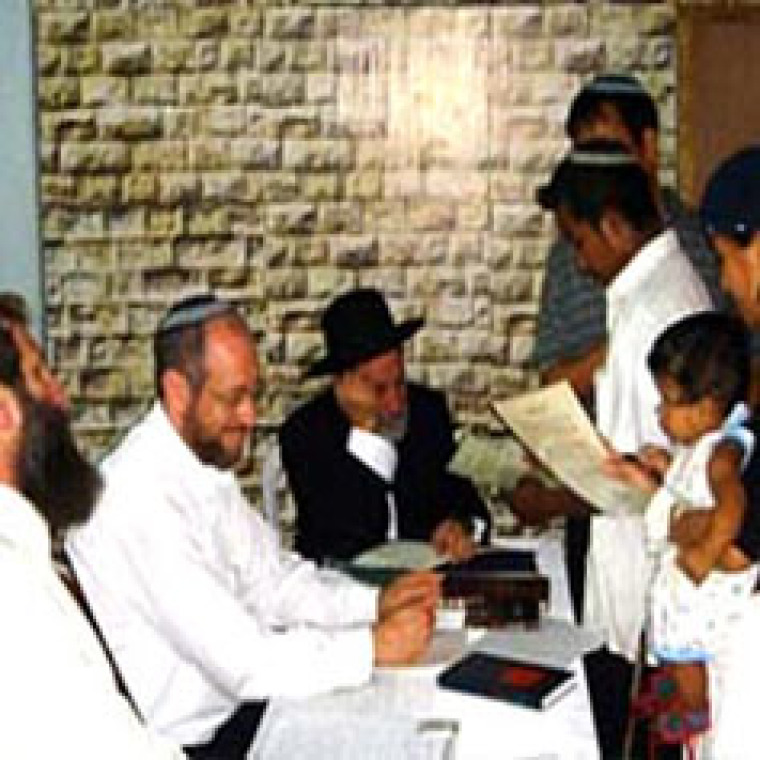

And now, the arrival of the official delegation or a beit din (rabbinical court) in northeast India to formally convert the tribe to Orthodox Judaism, has paved the way for the tribe to apply for immigration to Israel under the Law of Return, which grants the right of citizenship to all Jews.

"The rabbinic delegation is a historic turning point," said Michael Freund, chairman of Shavei Israel, the Israeli group that has arranged the tour. "It is comforting to see the words of the prophets are coming true before our very eyes with the journey home to Zion of this lost tribe."

Six rabbis, appointed by Shlomo Amar, in conjunction with Shavei, are now in India to begin converting the members of the Bnei Menashe tribe. According to news reports, the rabbis met with hundreds of tribal members, testing their knowledge of Judaism and assessing their conviction, converting two hundred individuals – over 90 per cent of those who were interviewed. The candidates rejected were told to continue to study Jewish tradition for reassessment upon the rabbis' next trip.

"The rabbis were incredibly impressed with the Bnei Menashe," said Freund. "They saw for themselves that the group is very serious, and should be integrated into the Jewish nation."

Now officially Jewish, the 200 converts are all set receive financial and other aide from Freund's group.

After Israel's Interior Ministry allocated an annual quota of 100 immigrants from the Indian tribe in 1993, Shavei Israel has helped about 800 Bnei Menashe young men and women convert and settle in Israel — mostly in the occupied Palestinian territories.

But in 2003, when the Interior Ministry decided to end the Bnei Menashe aliyah ("right of return" to Israel), Shavei Israel activists started intense lobbying through the chief rabbinate to get the Indian group accepted by Israel as one of the lost tribes. They succeeded when the March announcement came from the chief rabbinate.

"The latest events with the chief rabbinate helps so much," said Freund. "In another few years, I am certain the rest of the Bnei Menashe still in India will return home to Zion."

Surojit Chatterjee

Christian Today Correspondent