Myanmar has been in the news recently, after a coup carried out by the Tatmadaw (Burmese military) on 1 February 2021, overturning the elected government and preventing recently elected lawmakers from opening a new session of Parliament.

The country’s elected leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and members of her party are now under house arrest. As a result, all ethnic and religious minorities as well as actors of conscience and conviction are in grave danger, although the situation has mobilized many ‘grassroots’ people to act.

Background

Suu Kyi, 75, a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, won a landslide election victory in 2015 after 15 years of house arrest and after more than half a century of military rule beginning in 1962. Read here a timeline of key developments up to 2015.

Suu Kyi has tried to placate the military and demonstrate her regard for its important role in maintaining the country’s security. She is the daughter of Aung San, the founder of Myanmar’s military, and she no doubt feels an obligation to maintain its prestige and prominence. This has probably led to the poorly written constitution.

Weaknesses in the constitution exploited

The weaknesses in the Myanmar constitution were clear even when it was ratified in 2008. It allowed the military to take power during a "state of emergency." In addition, a quarter of the parliamentary seats were reserved for the military, including the key ministries of defense and foreign affairs. Most important, the document didn't guarantee that all people living in the country were eligible for citizenship.

The international community could have put pressure on the military to change its behavior and help draft a proper constitution that enshrined the rights of all its citizens when the country finally adopted democracy in 2010. But despite the obvious inhumaneness of this, the international community took few steps to try to change the document or its application.

Instead, the military, while no longer officially ruling the country, was allowed to retain its power and grow its influence. Most significantly, in 2017, it launched an ethnic cleansing operation in the western state of Rakhine that led to the exodus of the Rohingya minority. This travesty was both a direct sign of the failures of the constitution and a warning to the international community that it had to act if Myanmar were to stay a democracy. But the international community did little other than condemn the violence.

The coup and the protests

The junta said it was forced to step in because Suu Kyi’s government failed to properly investigate allegations of fraud in recent elections, though the electoral commission has said there is no evidence to support those claims.

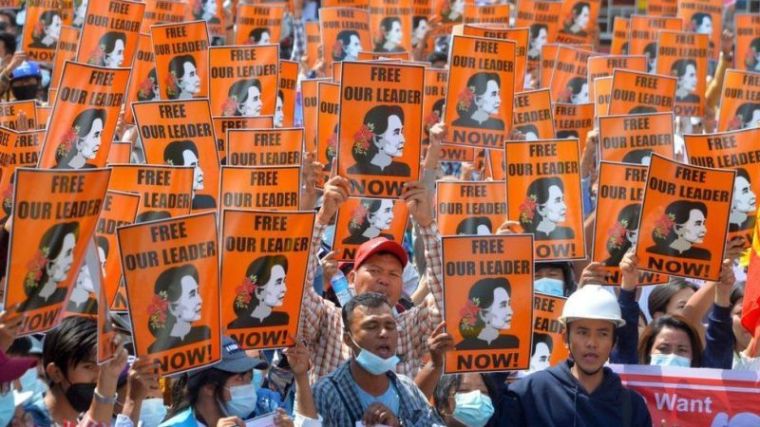

In response to the coup, tens of thousands of protesters have marched daily in Yangon and Mandalay, the country’s biggest cities — and the demonstrations have spread throughout the country, showing depth of the resistance. The rallies have drawn people from all walks of life, despite an official ban on gatherings of more than five people. Factory workers and civil servants, students and teachers, medical personnel and people from LGBTQ communities, Buddhist monks and Catholic clergy have all come out in force.

Thinzar Shunlei Yi, a human rights activist in Yangon, called what was happening a repeat of history in reference to the National League for Democracy party's 1990 landslide election. The same tactic was used when the military didn’t like the results of the election and there is concern about how long it will last.

The crackdown against anti-coup protesters in the mostly Burman-Buddhist cities of Yangon (Rangoon) and Mandalay is being widely reported by mainstream media. However, the situation in Burma's ethnic minority states - where most of the country's Christians live - remains dark.

Yet it is in these ethnic minority states that the Tatmadaw (Burmese military) has long committed its worst crimes - bombing and burning villages, killing, torturing and raping civilians - with impunity. The barbarity with which the Tatmadaw commits these crimes is the product of its covetous greed and its Burman-Buddhist ethnic-religious supremacism.

The coup leaves Myanmar's long-persecuted Karen, Kachin and Chin Christians gravely imperiled. Meanwhile, the ousted government has appointed Dr Sasa - an ethnic Chin and Christian - as its special envoy to the United Nations.

We need to pray that God will:

· intervene in Myanmar to redeem this crisis for his glory; may the Tatmadaw be restrained, and its power limited; may Burma's peoples unite around their desire for peace, justice, liberty and respect.

· embolden his Church to 'utter what is precious' and thus 'be as [the Lord's] mouth' during this crisis (from Jeremiah chapter 15, verses 15-21). May the Lord - who breaks through enemies like a breaking flood (2 Samuel chapter 5, verses 17-21) - open the way for the Church to receive all the humanitarian aid she requires; may many fearful, confused and needy people find Jesus in the midst of this storm (see Matthew chapter 14, verses 22-33).

· accompany and protect Dr Sasa, and fill him with wisdom, discernment and courage as he represents Myanmar's elected government and citizens on the international stage.

God loves importunate [persistent] prayer so much that He will not give us much blessing without it.' (Adoniram Judson, 1788-1850; pioneer missionary to Burma).

For this plus more detail, including images, maps, hyperlinks and archives, see: Religious Liberty Prayer Bulletin (RLPB) 587. Burma (Myanmar): Christians Imperiled (3 March 2021).

Aira Chilcott is a retired secondary school teacher with lots of science andtheology under her belt. Aira is an editor for PSI and indulges inreading, bushwalking and volunteering at a nature reserve. Aira’s husband Bill passed away in 2022 and she is left with three wonderful adult sons and one grandson.

Aira Chilcott's previous articles may be viewed at http://www.pressserviceinternational.org/aira-chilcott.html